Shipwrecks

THE GRAVEYARD OF THE PACIFIC

It is estimated that 2,000 ships and hundreds of lives have been lost along the stretch of coast from Oregon to British Columbia. For this reason it is sometimes called, “The Graveyard of the Pacific.” The ever-present fog, shifting sands and treacherous currents have claimed at least two hundred ships near the mouth of the Columbia River. The North Head Lighthouse stands guard right in the middle of this notoriously dangerous area.

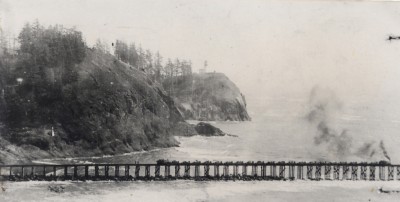

There have been many attempts to tame the mouth of the Columbia River. The system of jetties was built (1885-1917) to control the sand bars and make the river’s channel deeper and more stable. The US Lifesaving Service, and now the Coast Guard have saved thousands of lives from these dangerous waters. Several other lighthouses, including Cape Disappointment Lighthouse and the Columbia River Lightship were placed around the river’s mouth to try and make it safer for maritime traffic. But the ships still got stuck.

Before the jetties were built, the mouth of the Columbia River was even more dangerous than it is today. There were sand spits extending into the ocean from both the north and south sides of the entrance with a large sand island blocking the middle. The two channels wound around the spits and island; their locations and depths were unpredictable. In 1841, while the US Exploring Expedition was charting the channels, the US Peacock wrecked on the sand spit off Cape Disappointment. Since then, this shallow area has been called, “Peacock Spit.” As ship traffic increased around the turn of the century, so did the frequency of shipwrecks. The narrow beach and rocky coves below North Head became known as “Deadman’s Hollow.”

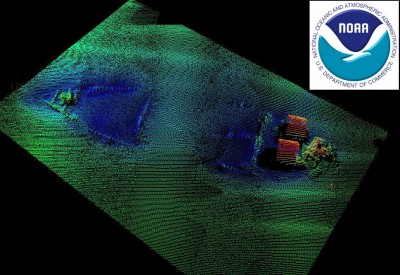

After the jetties were completed, 1,000 acres of sand built up behind the North Jetty in a little over a decade. In 1930, the Admiral Benson, a steamship coming down the coast from the north attempted to safely navigate into the Columbia River. Three hundred yards west of the tip of the North Jetty it struck the remains of the Laurel, a ship that had sunk there a year previous. The 65 crew members and 39 passengers were rescued within the day but the captain stayed on board, hoping the ship could be salvaged. A week later he gave up on his ship. Within months, the remains of the Admiral Benson were sucked into the sands of Peacock Spit where they remain to this day. Benson Beach, between the North Jetty and North Head was named for this shipwreck.

Article: U.S. Coast Guard opens National Motor Lifeboat School at Ilwaco in 1980.

Shipwrecks are not all so historic. In 2005 the barge Millicoma parted from its tug boat while crossing the Columbia River bar. It took most of the night to drift, unmanned, into a rocky cove directly north of the North Head Lighthouse. Fortunately, the barge had only enough diesel fuel on board to run its equipment and the base of the cove was sandy. Three days later, the salvage operation successfully pulled the barge out of the cove. After pumping the barge with air to make it more buoyant, the Salvage Chief and three other tugs were able to safely pull it off the sand, around the jetties, up the Columbia and docked it in Astoria for minor repairs. Even with the jetties, Coast Guard, dredgers and multiple lighthouses, ships still get stuck in the Graveyard of the Pacific.

To learn more about the maritime history of the Columbia-Pacific region while at Cape Disappointment State Park, visit the Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center. Although the majority of the exhibits interpret the Lewis and Clark Expedition, this recently renovated facility also includes maritime exhibits. One of the cherished items on display is the 1st-order Fresnel lens that was in both Cape Disappointment and North Head Lighthouse. In addition, a century old US Lifesaving Service surf boat and shipwreck artifacts can be seen including items from the Admiral Benson.

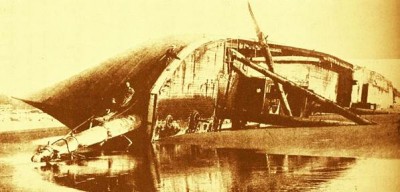

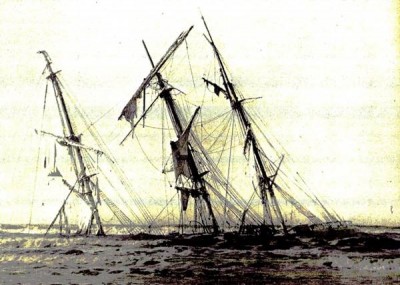

Historic Shipwreck Images

Read about the Schooner North Bend

Read about the Schooner North Bend

The Columbia Pacific Heritage Museum has a wealth of historic photos available by research request.